On starchitects, domestic violence, and the Stockholm Syndrome.

Le Corbusier. Frank Lloyd Wright. Louis Kahn. Great architects. Lauded visionaries. Master womanizers and manipulators. The film “My Architect”, a documentary about the life of Louis Kahn, provides a disheartening case-in-point.

The film summarizes Kahn’s life: immigrating to the US from Estonia as a five-year old, he grew up poor in North Philadelphia, moving around a lot, but showing an early talent for art.

See also: 10 facts about infidelity

Laurie Penny on the sex lives of powerful men

Many Mansions: On the centenary of Louis Kahn’s birth, a look at his legacy. And his secret life.

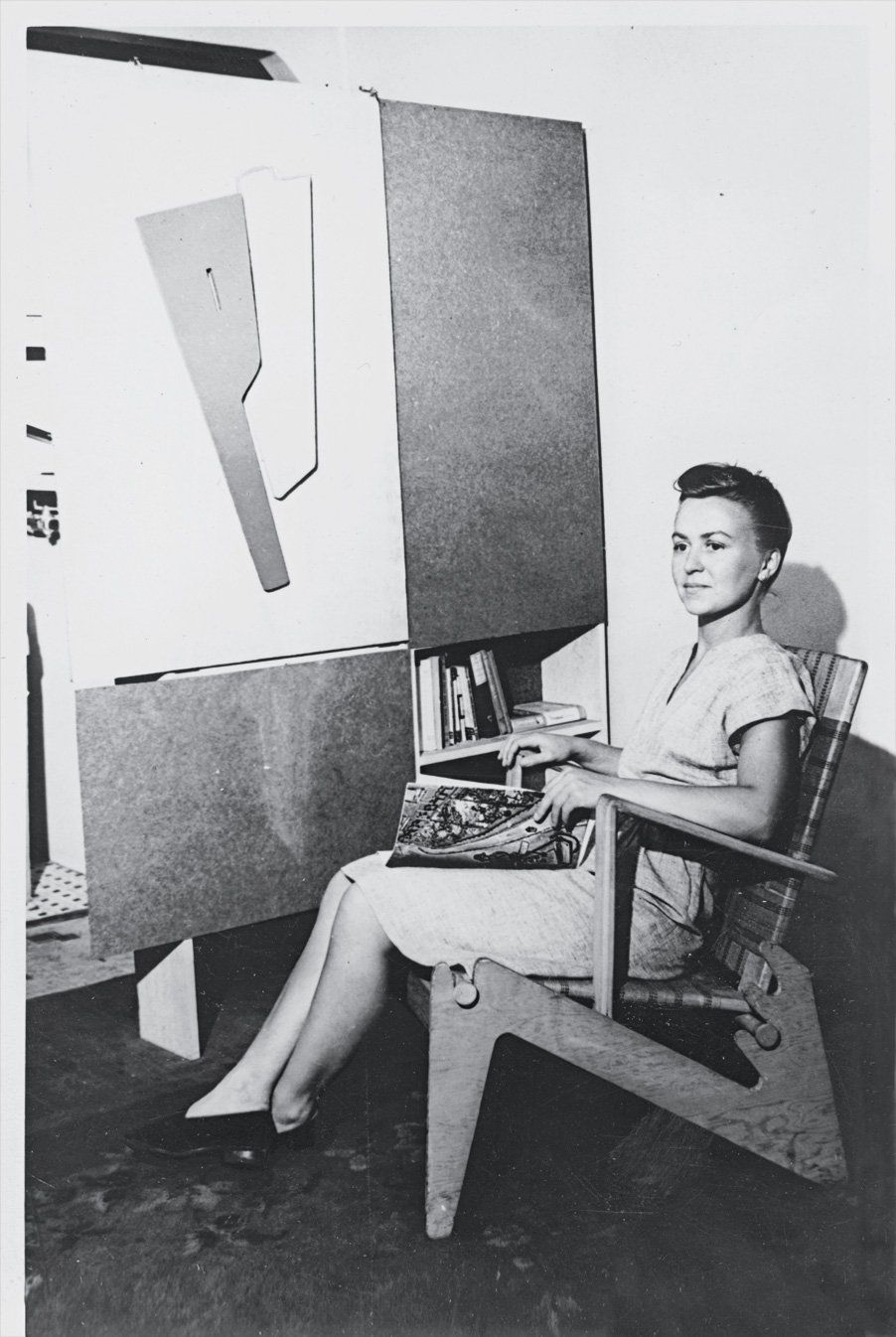

He eventually earned a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied architecture. He opened a studio in Philadelphia, but didn’t gain notoriety until reaching his 50s. By that time, he also had three children, each by a different woman. The first to whom he remained married; the second whom he ditched for the third; the third whom he strung along until his death in 1974 ((Anne Tyng, a renowned architect in her own right and mother of his second child, pictured above).

The combination of “Stockholm Syndrome” and “cognitive dissonance” produces a victim who firmly believes the relationship is not only acceptable, but also desperately needed for their survival. The victim feels they would mentally collapse if the relationship ended. In long-term relationships, the victims have invested everything and placed “all their eggs in one basket”. The relationship now decides their level of self-esteem, self-worth, and emotional health.

– The Stockholm Syndrome: The Mystery of Loving an Abuser

For me, the film unfolded under the dark shadow of male power and naïve female subservience. What is it about women who tolerate, make excuses for, and madly love abusive philanderers, regardless of their own well-being, or that of their children (I ask as a statistic myself, having ended abusive relationships, but never tolerating or excusing, let alone continuing to love the perpetrator)? Do they derive power, prestige, and pleasure from the dysfunctional relationship? Was their 15 minutes of fame in a beautifully-made documentary worth a lifetime of deceit and regret, never mind being portrayed as pathetic fools? All three of these women appeared sad and tragic, not a legacy I choose to leave. But which makes me wonder: is loving someone great inherently more passionate and invigorating than loving someone ordinary? Does greatness require willing recipients for acts of abuse? Surely not.

- Portrait of Esther and Louis Kahn, Kahn’s only wife and the mother of his first child. Photo via the University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives.

- Harriet Pattison, mother of Kahn’s third child, Nathaniel, director of “My Architect”.

How do we as a society evolve to expectations of more egalitarian, functional relationships? How do we empower girls to reject these outdated, mysogynistic relationship models? How do we educate boys of the same?

How do girls gain confidence and self-esteem, thus empowering them to unapologetically reject any man who treats her less than a full equal? And though one might argue that infidelity alone doesn’t classify as domestic violence, I argue that it does fall under the domestic violence umbrella, on one end of a long and complicated spectrum.

The types of behaviour associated with coercion or control may or may not constitute a criminal offence in their own right. It is important to remember that the presence of controlling or coercive behaviour does not mean that no other offence has been committed or cannot be charged. However, the perpetrator may limit space for action and exhibit a story of ownership and entitlement over the victim.

– In 2016, the UK expanded its legal definitions of domestic violence.

Being a hero of any discipline does not give license to abuse. While I may appreciate the design philosophies of Louis Kahn, he will never be one of my design heroes. His forms, while noble in theory, are ugly; his lack of personal ethics, reprehensible.