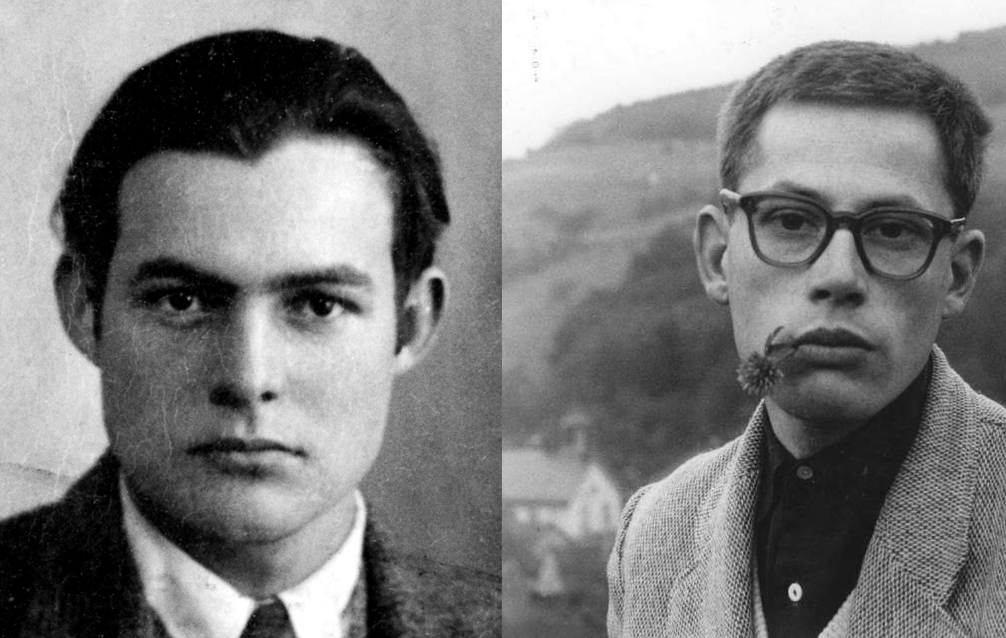

On what designers can learn from icebergs and Ernest Hemingway.

My favorite passages In Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast are the direct, austere descriptions of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Painting vivid pictures with minimal words is the hallmark of Hemingway’s writing, which he developed into The Iceberg Theory.

Write like Hemingway! The Hemingway App.

The Iceberg Theory (also known as the “theory of omission”) is the writing style of American writer Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway began his writing career as a reporter. Journalistic writing, particularly for newspapers, focuses only on events being reported, omitting superfluous and extraneous matter. When he became a writer of short stories, he retained this minimalistic style, focusing on surface elements without explicitly discussing the underlying themes. Hemingway believed the true meaning of a piece of writing should not be evident from the surface story; rather, the crux of the story lies below the surface and should be allowed to shine through.

—Wikipedia

and

Hemingway said that only the tip of the iceberg showed in fiction—your reader will see only what is above the water—but the knowledge that you have about your character that never makes it into the story acts as the bulk of the iceberg. And that is what gives your story weight and gravitas.

—Jenna Blum in The Author at Work, 2013[9]

See also: The Age of Invisible Design

How can designers apply The Iceberg Theory to design work? What does it mean to show only what’s useful and meaningful in the tip of a product design iceberg? What does giving weight and gravitas through omission look like in product design? We can start by looking to Dieter Rams, who is to design what Ernest Hemingway was to writing:

‘Good design is as little design as possible’ is one of Dieter Rams’s most famous and favourite phrases. He means this in the sense that a well-designed product should be so good that it is barely noticeable. By omitting the unnecessary, says Rams, the essential factors come to the fore: the products become ‘quiet, pleasing, comprehensible and long-lasting.’ However, to arrive at products with this quality the design has to travel a very long and difficult path filled with questions, trials, discussion, and experimentation. The product may be simple, but the path taken to create it is highly complex for the ‘true’ product designer. Rams explains: ‘Product design is the organisation of the product in its entirety so that it fulfills its respective function as well as possible. At the same time, this design must meet the factual terms and conditions under which the product can be brought on to the market. Designers that confront this task have nothing to do with those who may call themselves designers, but only concern themselves with a retrospective clothing of products purely according to criteria of taste.

—Sophie Lovell in Dieter Rams: As Little Design as Possible